A Research Site Devoted to the Past and Future of Found Footage Film and Video

“A lot of people who call themselves artists now are cultural critics who are using instruments other than just written language or spoken language to communicate their critical perspective.”

-Leslie Thornton

Tuesday, December 9, 2008

Digital Remixing from the Picket Lines

In the midst of this, renowned video artist John Greyson, whose incredible commitment to appropriation can be discerned from his film manifesto on cultural recycling "Uncut" (1997, has created a digital remix to support the strikers.

Please watch:

Saturday, November 8, 2008

My War with Chevrolet on Wikipedia

You may all remember my posting last year detailing Chevrolet's viral marketing campaign which spawned several hundred parodies and resulted in some very bad publicity for the company. If you don't, you can read the wikipedia post about this below. Several months ago, this page had all the details about the embarassment this caused but when I returned to the page last week it had been scrubbed. I re-entered this information and ONE DAY LATER it was scrubbed again. I think these commercials were a landmark moment for digital remixing and hope that anyone reading this now might go to the Tahoe wiki page and make sure the company isn't pulling more funny business.

Thanks!

The Apprentice make-your-own-ad contest

The 2007 Tahoe was featured on and promoted through Donald Trump's TV series, The Apprentice, where the two teams put together a show for the top General Motors employees to learn about the new Tahoe. Also, The Apprentice sponsored an online contest in which anyone could create a commercial for the new Tahoe by entering text captions into the provided video clips; the winner's ad would air on national television. This viral marketing campaign backfired however, when hundreds of environmentally conscious parodies flooded YouTube and Chevy's website critiquing the vehicle for its low gas mileage. Though Chevrolet initially made a statement saying they would keep these adds on their site the company eventually took them off. The negative publicity that these commercials garnered eventually led many marketing and p.r. firms to question the effectiveness of user generated advertising.

Tuesday, October 14, 2008

Peter Tscherkassky and Gustav Deutsch: The Contemporary European Contingency

Outer Space (Peter Tscherkassky)

Happy End (Peter Tscherkassky)

180º - Investigação de Gustav Deutsch (Nuno Lisboa)

Gustav Deutch- review - Borealis ´06

Thursday, September 11, 2008

Wednesday, August 20, 2008

Monday, August 18, 2008

Mondegreens, Animutation, Fanimutation and YouTube Poop

On the margins of these experimental works lie remixers who have coined their own grammar and style which lie outside of any precedent set in found footage film history. These remixers trade on the humor, absurdity and unbridled originality of their works for their success. A quintessential figure in this area is Buffalax (AKA Mike Sutton), whose name has become a verb in many remixing circles after receiving over ten million views since 2008. A Buffalax film depends on humorous mondegreens (a word referring to misheard lyrics or phrases) of Indian pop music videos which are subtitled on the bottom of the screen. Sutton inventively finds English words which seem to roughly approximate the Hindustani lyrics, constructing absurd songs over hysterically kitschy videos. This mode of filmmaking stems from comedian Neil Cicierega’s “animutations” (also known as fanimuation) in which music in languages other than English are coupled with pop-culture images, subtitled with mondegreens and composed using Adobe Flash Player.

Below are some examples:

Monday, July 28, 2008

Cut-Ups and Mashups

Thursday, July 10, 2008

Eat This Dow Chemical and Chevron

This campaign is strikingly similar to Chevron's "Power of Human Energy" campaign which receives an "identity correction" from one of our favorite remixers, Jonathan McIntosh. We Love you Jonathan!

Monday, July 7, 2008

BRUCE CONNER (1933-2008)

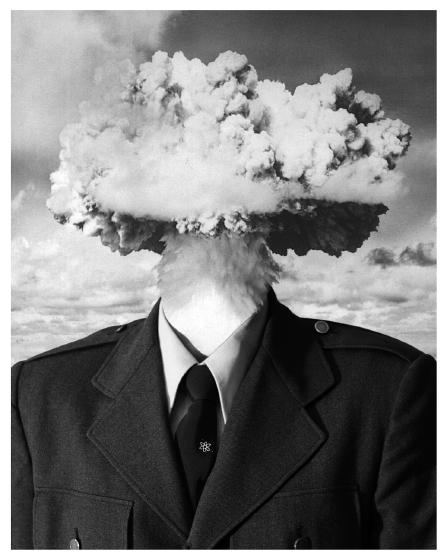

If you didn't already know how much Bruce meant to me personally, the image at the head of my blog says it all. Bruce made startling and thoughtful images that reflected on consumerism and capitalism with a playful derision and incredible inventiveness and ingenuity. He single handedly revived the found footage film with his 1958 work ironically called A Movie and went on to create some of the most important avant-garde films in America.

We miss you Bruce.

More to come on this later...

Sunday, June 29, 2008

2 New Offerings: Ikat381 and a new essay on Appropriation

Another gem from Ikat381.

Below is an essay I wrote concerning early modes of cinematic appropriation focusing on Joseph Cornell and the Soviet Re-editors.

“Everyone who has had in his hands a piece of film to be edited knows by experience how neutral it remains, even though a part of a planned sequence, until it is joined with another piece, when it suddenly acquires and conveys a sharper and quite different meaning than that planned for it at the time of filming.”[1]

– Sergei Eisenstein

Monuments to every moment,

refuse of every moment: used

cages for infinity. [2]

– Octavio Paz “Joseph Cornell: Objects and Apparitions” (1974)

Found footage filmmaking “has been a central genre of cinematic exploration for the American avant-garde in the postwar period”[3] with a significant increase in practitioners across North America and

The appropriation and transformation of extant film footage was a dominant feature of early Soviet cinema under the directive of the USSR State Committee for Cinematography (Goskino). Newsreel editors at the Export-Import division compiled disparate images for politically charged weekly news programs to screen to audiences across

Though the newsreel compilation preceded re-editing, the former’s status as a type of documentary is cause for its omission in relation to Cornell’s transformations. It should be noted however that the newsreel is the original pioneering site for found footage[9] and that the use of footage for an early form of documentary has had an impact in the way it was used for re-editors. Critic Paul Arthur writes:

Found footage was established as an integral element of exposition and argument, often serving as illustration of a verbal reference or as a means of filling gaps in spatial continuity or didactic evidence. Indeed, the recent outpouring of wartime newsreel compilations and military training films had underscored the importance of found footage to the rhetorical strategies of corporate and state-sponsored propaganda…[10]

The re-edited feature film has many similar features, though it holds no pretense towards documentary. As Arthur notes, the use of found footage as a powerful tool for government propaganda would become the primary impetus to transform western films. It is worth noting here that the Surrealist film exhibition in which Rose Hobart was first screened was called “Goofy Newsreels” in tribute perhaps to the earliest known form of found footage filmmaking.

While the Soviet practice may employ the tactics of propaganda and even censorship—editors also infused sophisticated new reading into films, dismantling what they saw as capitalist propaganda and replacing it with their own pro-Marxist versions. These re-editors were charged with transforming western films for Soviet audiences both to reflect Marxist ideals and to confirm Soviet suspicions about western capitalism. Many western films were radically altered through sophisticated editing techniques, transformations in intertitles and complete excising of certain characters.

Among the various changes re-editors were charged with making:

happy endings would be removed as suggesting that one can be happy under capitalism…"American endings" were generally believed to be forced upon artists by the capitalist film industry'… '[f]at and virtuous people were turned into villains as a general rule…. characters' nationality would be changed…[11]

These daily transformations developed in editors, not only a sophisticated ability to analyze the political meanings of films but also mastery in the area of montage. Discussing re-edited works alongside newsreel films may seem strange for the simple fact that re-editing does not initially strike one as a form of appropriation. Though the re-editors did not necessarily place their names on the films they altered, their transformation of films is itself a method of appropriation. The constellation of new ideas of form, interruption, appropriation and the reconstitution of meanings onto film objects become the foundation for the aesthetics and theories surrounding found footage filmmaking and may be seen as an application of Marxist aesthetics onto the new art form of the 20th century.

Marxist critic Walter Benjamin’s body of work often touches upon ideas of reuse, reproduction and authorship which pertain to the appropriation of images. The dialectical image was Benjamin’s model for historiography in The Arcades Project, which critic Jeffrey Skoller describes: “Benjamin suggests that to explore what an object from the past means in the present is to turn that object into a text that has at its center an imagining subject who finds new possibilities for its meaning.”[12] In this way, we might understand the re-edited film as the re-imagined film—a malleable source text reconstructed to fit a reading. Esther Shub’s Fall of the Romanov Dynasty might be best understood as dialectical image making specifically in her exploration of the recent Tsarist past through the prism of the post-revolutionary

In The United States, a young artist named Joseph Cornell would expand on the Soviet ideas with his poetic transformation of an early talkie picture called East of Borneo (1932). Though Joseph Cornell’s status as a member of the Surrealist movement was never official, he was closely allied and influenced by Surrealist artists and collectors—showing his work in the first American exhibition of Surrealist art in 1932 at the Julien Levy Gallery in

All of these features and strategies would make way for his pioneering film Rose Hobart, first screened in 1936 at the Julien Levy Gallery to a room full of Surrealists and resulting in the violent envy of one member of the audience; Salvador Dali.[13] The film was composed of images from an early talkie recovered by Cornell from a production archive selling the film for its nitrate stock. Cornell’s film, like many of his assemblages, is a tribute to an actress, Rose Hobart, the star of East of Borneo, whom Cornell transforms into a very different kind of heroine. The film was a culmination of Cornell’s appropriation of images into cinematic form which would leave a rich legacy for future cinematic appropriators and found footage filmmakers like Bruce Conner, Ken Jacobs, David Rimmer and Craig Baldwin. While the Soviets were predominantly interested in ideological transformation that was hidden[14] within the narrative of a film, Joseph Cornell would highlight his alterations by conspicuously slowing the footage down, replacing the original soundtrack, altering the color (with blue tinted glass) and constructing his own idealized and poetic homage to the main actress, Rose Hobart.

Narrative, Montage and Interruption

While the Soviet re-editors and newsreel creators were attempting to produce or maintain narrative, Cornell’s collage film pursued what P. Adams Sitney calls a “surrealist narrative”[15] which shatters logical narrative progressions utilizing the language of associative images and the grammar of fragmentation. The features which unite these two approaches appear in the idea of montage. Critic Yuri Tsivian suggests

that the innovative Soviet editor Viktor Shklovsky:

“understood art as a special way of assembling things and enjoyed watching the whole change its meaning as he rearranged its parts on his editing table. For a theorist, this process confirmed what Kuleshov (pioneer re-editor..) had earlier shown about cinema and what Tynianov had found about the language of poetry in 1923, namely, that ‘meanings’ are generated through juxtaposition and foregrounding:”[16]

Numerous Soviet montage theorists suggest that montage is essentially the act of assembling meaning through the technique of juxtaposition. Eisenstein suggested that cinema should follow the methodology of language rather than theater and painting because it would allow “wholly new concepts or ideas to arise from the combination of two concrete denotations of two concrete objects…”[17] If we accept Eisenstein’s characterization of film as “a language…in which the real is used as an element of a discourse”[18] this language of montage is similar to the language of collage and assemblage, though it does not immediately suggest materials culled from disparate sources. The primary difference might be in the Soviet use of montage to illustrate rational associations for the purposes of narrative progression while Cornell was interested in montage that illustrated the logic of dreams.

Interestingly, Cornell does include one very famous sequence of narrative cohesion, if it might be called that, surrounding one of the major motifs of Rose Hobart. The film opens with a crowd gazing into the sky, which critic Jodi Hauptman suggests represents a kind of “stargazing” befitting not astral bodies but actual movie stars—like Rose Hobart.[19] This stargazing culminates in an eclipse at the end of the film, in which “just after the moon completes its passage in front of the sun, the sun appears to drop into a pool of water.”[20] This editing sleight-of-hand establishes one of the most compelling and imitated techniques in found footage filmmaking—the conjoining of film fragments which when put together indicate a narrative cause-and-effect but are nonetheless quite illogical.

Hal Foster describes Surrealist collage as “a disruptive montage of conductive psychic signifiers (i.e., of fantasmatic scenarios and enigmatic events) referred to the unconscious.”[21] Cornell uses major tropes of East of Borneo and mines them for their associative and metaphorical properties. As Hauptman illustrates in her brilliant book on Cornell and cinema, “the hysterical body of the woman is associated with and echoed metonymically by another site of otherness: the ‘primitive’ island kingdom”[22] in which

The actress wanders through a nighttime dreamscape: so many unexplained events, the sublime mystery of an eclipse, the concentrated look of the exotic Prince; but nothing ever gets going. All meanings are thwarted, and all linear narrative and causality is deliberately defied.[24]

The shattering of narrative logic, the disruption of continuity and the conjoining of associative images distinctly indicates the province of not only of Surrealist montage but of a frequent interruption of meaning and narrative—forcing the spectator to reorient herself throughout the 19 minute film.

The “wise and wicked game” of wit that Sergei Eisenstein refers to in discussion of the re-editors has no place in the aesthetics of Joseph Cornell who uses the rhetoric of dream, portraiture and Surrealist collage in his film. Cornell achieves these fractured images by juxtaposing fragments which have no coherent “logical” meaning. This radical juxtaposition of images for the production of alternative meanings was also a strategy employed by the Surrealists in numerous instances and prominently by collagist Max Ernst. Cornell’s encounter with Ernst’s collages was the inspiration for his entire career—turning him into a devout, albeit weary, disciple of Surrealism. It was Ernst’s La Femme 100 têtes, a Surrealist collage novel composed of fragments from “Victorian steel engravings from old catalogues, magazines, and pulp novels”[25] that would capture Cornell’s attention and entice him to begin using his own vast collection of materials in his work. Surrealist games like the Exquisite Corpse which sought to produce radical combinations of images, or the jarring and radical collages which in Max Ernst’s words created the “coupling of two realities, irreconcilable in appearance, on a place which apparently does not suit them” [26] were all an influence on Cornell’s assemblages.

Beyond Cornell’s achievement in developing a new form of cinematic appropriation in Rose Hobart, it is also important to consider the intricate montage he constructs for the film, characterized by P. Adams Sitney here:

Cornell’s montage is startlingly original. Nothing like it occurs in the history of cinema until thirty years later. The deliberate mismatching of shots, the reduction of conversations to images of the actress without corresponding shots of her interlocutor, and the sudden shifts of location were so daring that even the most sophisticated viewers would have seen the film as inept rather than brilliant…. The editing of Rose Hobart creates a double impression: it presents the aspect of a randomly broken, oddly scrambled, and hastily repaired feature film that no longer makes sense; yet at the same time, each of its curiously reset fractures astonishes us with new meaning. [27]

Sitney’s authoritative defense of the film’s editing is important. Rose Hobart is frequently discussed only for its contribution to the idea of found footage film and cinematic appropriation rather than for the merits of the incredible montage the inexperienced Cornell composed. The language of the film may be appropriated film fragments, but the grammar creates a sophisticated interplay of those fragments and constitutes a highly original development in film montage.

Transformation, Appropriation and Cultural Resistance

The difference identified in the two aforementioned approaches towards appropriation relates to whether or not a transformation works within the system of the material appropriated. In other words, is the artist appropriating both images and structure? In Cornell’s case the answer clearly is no—as evinced in the narrative disruption, the elimination of sound and the break from

Soviet film transformations had many incarnations and utilized a variety of source materials which extended from altering contemporary stories to, in the following case, introducing varying attitudes towards history. Eisenstein gives an anecdote to explain just how this was performed with the German film Danton (1924) which dramatized events during the French Revolution. Eisenstein explains a transformation that dramatically alters the film:

Camille Desmoulins is condemned to the guillotine. Greatly agitated, Danton rushes to Robespierre, who turns aside and slowly wipes away a tear. The sub-title said, approximately, 'In the name of freedom I had to sacrifice a friend ...' Fine. But who could have guessed that in the German original, Danton, represented as an idler, a petticoat-chaser, a splendid chap and the only positive figure in the midst of evil characters, that this Danton ran to the evil Robespierre and ... spat in his face? And that it was this spit that Robespierre wiped from his face with a handkerchief? And that the title indicated Robespierre's hatred of Danton, a hate that in the end of the film motivates the condemnation of Jannings-Danton to the guillotine?![29]

The re-editors turned Danton’s spit into a “tear of remorse” through minor alterations which transformed the meaning of the film to reflect positively on Robespierre. This kind of transformation does not only interject a Marxist reading, it in effect creates a kind of revisionist history sympathetic to their view of the French revolution.

Critic Hal Foster makes a case that appropriators find the locus of their power in their ability to reconstitute meanings onto signs and disrupt the “monopoly of the code”[30] by an elite of cultural producers. Foster invokes Baudrillard’s assertion that “semiotic privilege represents… the ultimate stage of domination”[31] and makes a case that appropriation can disrupt the bourgeoisie’s “mastery of the process of signification.”[32] In this way, we might understand appropriation as a means of cultural resistance through the attempt to subvert meanings and control signification. The appropriator can impose new meaning or disrupt accepted meaning through inventive transformation.

As the Soviet editors from Goskino had been given ideological control over the import of Western films by the government, it may appear difficult to justify their transformations as cultural resistance unless we consider the global cinema of this era as dominated by pro-capitalist ideology. If we observe the Soviet re-editing experiment as a way of subverting the pro-capitalist cultural domination of Western films, the idea of cultural resistance could be accepted on a national scale. The Soviet control of signification, however, did not allow for an unchanged referent (i.e., the original film) alongside the altered film for the spectator to compare the transformation—unlike Joseph Cornell who uses a film which was widely released in The United States. In this way the re-edited films of the Soviet era also posses a sinister side—a form of cultural engineering, censorship or propaganda.

In the case of Joseph Cornell, the appropriation of East of Borneo represents a highly successful example of overthrowing the ‘monopoly of signification.’ For its time, Borneo was a major

Conclusion: The Legacy of Cornell and the Soviet Re-Editors

To conclude, it seems appropriate to briefly touch upon the legacy these two approaches have left for avant-garde cinema. While found footage films in the last half century have frequently featured heavy cross-pollination between the two approaches discussed above, many explicitly borrow from traditions pioneered by either Cornell or the Soviet re-editors. Contemporary found footage filmmaker Craig Baldwin might be described as utilizing both approaches in his left-wing pseudo-historical documentaries which utilize a vast array of images as source material for their associative properties. Perhaps the most well known avant-garde found footage film, A Movie (1958) by Bruce Conner, features sequences which attempt to construct narrative in a highly surreal fashion similar to Cornell’s editing sleight-of-hand with the “falling eclipse” in Rose Hobart. This famous sequence is explained by critic William Wees: “A submarine captain seems to see a scantily dressed woman though his periscope and responds by firing a torpedo which produces a nuclear explosion followed by huge waves ridden by surfboard riders.”[35] Each new scene comes from a disparate film but has a surreal narrative concatenating the scenes. A direct descendent of the Soviet re-editing style is observable in Can Dialectics Break Bricks (1973) by Situationist filmmaker René Viénet. The film appropriates images from a Korean kung-fu film and interjects a Marxist narrative about a group of disenfranchised factory workers and their battle with wealthy bureaucrats through Hegelian dialectics—all achieved through the re-dubbing of the film’s soundtrack. Ken Jacobs cites Cornell as one of his primary influences and even calls his film A GOOD NIGHT FOR THE MOVIES: The Fourth Of July by Charles Ives by Ken Jacobs “a sequel to Rose Hobart.”[36] Cornell’s mentorship of both Larry Jordan and Stan Brakhage, (whom he commissioned to make several of his film ideas) is also said to have guided the two young filmmakers towards their brilliant film careers.

Together, the approaches pioneered by the Soviet re-editors and Joseph Cornell seem to contain the foundations for some of the most radical manipulations of film footage in the history of the technique. The Soviet’s initiate a practice which offers appropriators the ability to facilitate cultural resistance towards dominant cinema and through wit, deconstruct and recreate footage so that it actually argues against its own claims—what some have called media jujitsu. Cornell moves from the nationalistic political arena of the Soviets towards a more personal conviction—which seeks to use film as a found object. Cornell’s transformation attempts to break through the façade of the cinema screen and portray the actress within it—to channel her as if through a dream from within the contrivances of a plot. Together, these two approaches leave a rich legacy and continue to teach artists about a form of filmmaking which requires little more than a flatbed and ingenuity.

[1] Eisenstein, Sergei. “Through Theater to Cinema.” in Film Form: Essays in Film Theory. Ed. Jay Leyda. Harvest Books:

[2] Paz, Octavio. “JOSEPH CORNELL Objects and Apparitions in Thories and Documents of Contemporary Art. Ed. Kristine Stiles and Peter Selz.

[3] Skoller, Jeffrey. Shadows, Specters, Shards: Making History in Avant-Garde Film.

[4] Wees, William C. “From Compilation to Collage: The Found Footage Films of Arthur Lipsett: The Martin Walsh Memorial Lecture 2007.” Canadian Journal of Film Studies, 16:2 (Fall 2007): 4

[5] Tsivian, Yuri. “The Wise and Wicked Game: Re-editing and Soviet film Culture of the 1920s”

Film History 8:3 (1996): 327

[6] Yutkevitch, Sergei. “Teenage Artists of the Revolution.” Cinema and Revoltuion.

[7] Leyda, Jay. Films Beget Films. Hill and Wang:

[8] Vertov, Dziga. “In Defense of Newsreel.” Kino Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov. Ed. Annette Michelson.

[9] According to Jay Leyda, this tradition can be traced back as early as 1898. See Leyda: 13

[10] Arthur, Paul. “The Status of Found Footage” Spectator - The

[11] Tsivian: 329

[12] Skoller: 5

[13] Dali claimed to Breton that “My idea for a film is exactly that, and I was going to propose it to someone who would pay to have it made…I never wrote it or told anyone, but it is as if he had stolen it.” Quoted in Solomon, Deborah. Utopia Parkway: The Life and Work of Joseph Cornell. Farrar, Straus and Giroux:

[14] Overwhelmingly these Soviet transformations were made so that audiences were unaware of them—however numerous cases of “private screenings” amongst editors highlighted in comedic ways, how these transformations occurred.

[15] Sitney, P. Adams. “The Cinematic Gaze of Joseph Cornell.” From Joseph Cornell. Ed. Kynaston McShine.

[16] Tsivian: 338

[17] Eisenstein, Sergei. “A Dialectic Approach to Film Form.” in Film Form: Essays in Film Theory. Ed. Jay Leyda. Harvest Books:

[18] Ulmer, Gregory L. “The Object of Post-Criticism.” In The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture. Ed. Hal Foster. Bay Press:

[19] Hauptman, Jodi. Joseph Cornell: Stargazing in the Cinema.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Foster, Hal. Compulsive Beauty. M.I.T. Press:

[22] Hauptman: 97

[23] Buck-Morss, Susan. The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the

[24] Rony, Fatimah Tobing The Quick and the Dead: Surrealism and the Found Ethnographic Footage Films of "Bontoc Eulogy” and “Mother Dao: The Turtlelike” Camera Obscura 18:1:52 (2003): 132

[25] Solomon: 57

[26] Hauptman: 33

[27] Sitney: 75

[28] Hauptman: 87

[29] Eisenstein. “Through Theater to Cinema.”: 11

[30] Foster, Hal. Recodings: Art, Spectacle, Cultural Politics. Bay Press: Port Townsend, 1985: 173.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Hauptman: 53

[34] Waldman, Diane. Joseph Cornell: Master of Dreams. Harry N Abrams Inc:

[35] Wees, William C. Recycled Images: The Art and Politics of Found Footage Films.

[36] Jacobs, Ken. “Painted Air: The Joys and Sorrows of Evanescent Cinema.” Millennium Film Journal 43-44 (Summer 2005): 53

Friday, June 13, 2008

Machinima and Up and Coming Work

Right now I'm working on a very time consuming and fragmented form of Recycled Cinema using 12-18 frame clips of people talking and synchronizing them into melodies. Though it can be deeply frustrating at times, the experience has revealed how speech is tonal and when isolated can become musical. I've always been very attracted to Martin Arnold's method of repetition to reconstitute meaning through fragmention, and it is a truly fun exercise to do on your own, but am trying to take his idea and isolate it from any semblance of narrative or meaning into a purely rhythmic collage of sound.

Most of my reading and writing right now is concerned with how Surrealists theorized found objects. The principal figures I'm looking at, Joseph Cornell and Marcel Duchamp were not officially inaugurated by Andre Breton into the Surrealist group but made some of the most interesting contributions to found object art with their assemblages and readymades.

Hal Foster's writing has been helpful, specifically the offbeat Compulsive Beauty which gives a very unusual treatment of Surrealism which largely abstains from the routine assessments we're familiar with. Perhaps it is Foster's willingness to look at the work and tendencies rather than Breton's public proclamations that make it so interesting. Also, I'm slightly puzzled by the density and impenetrability of Foster's Recordings: Art, Spectacle, Cultural Politics, but some passages and sections have been incredibly useful. I'm largely referring to how Foster suggests appropriation's greatest power is in recoding signs--in forcing encoders of messages to relinquish control. Foster argues that the control of meaning in artworks through appropriation is one of the most powerful forms of cultural resistance.

I'm writing right now on the split approaches of Soviet re-editors (which I've previously discussed) and Cornell's found footage film Rose Hobart when it comes to the strategies both employ. If anyone has tips of good books to look at Surrealist appropriation, shoot them my way.

Monday, May 5, 2008

Sunday, May 4, 2008

The Soviet Connection

Much of my work has attempted to draw parallels between contemporary video appropriation and transformation on the Internet with avant-garde found footage filmmaking. While I stand by these connections, the contemporary practice, which I call recycled cinema, has much in common as well with Soviet newsreel compilations and re-editing practices.

The use of appropriated footage in Soviet films has been traced back to a French worker from the Lumière factory, Francis Doublier who toured the Jewish districts of Southern Russia in 1898, showing films from his company’s cinematographe. During his tour, Doublier overheard complaints about the lack of images of the Dreyfus case, in its height at the time, and came up with a way of forging images by coupling various film clips of marching soldiers, ships in port and a scene of the Delta of the Nile. Critic Jay Leyda explains the effect:

In this sequence, with a little help from the commentator, and with a great deal of help from the audience’s imagination, these scenes told the following story: Dreyfus before his arrest, the Palais de Justice where Dreyfus was court-martialled, Dreyfus being taken to the battleship, and Devil’s Island where he was imprisoned, all supposedly taking place in 1894.

Doublier, described as “the spiritual ancestor” of Lev Kuleshov, the Soviet montage theorist, uses the metaphoric properties of film to analogize the event where images do not exist. This technique, described by critic Paul Arthur as “metaphoric fabrications of reality” becomes one of the initial attractions to using archival materials in Soviet non-fiction filmmaking.

Two departments of the Soviet film system theorized, experimented and produced what might now be the body of knowledge and practice that have defined the use of found footage in both documentary cinema and the experimental films of Europe and North America since the late 1950s. In the 1920s, the Soviet Export-Import Division of the “The Central State CinePhoto Enterprise (Goskino) founded with an eye, among other tasks, to monopolize distribution” dealt with re-editing films from capitalist countries to reflect pro-communist ideology and made exported films more palatable to international audiences. Newsreel editors, often times also re-editors under the Export-Import division, compiled film for weekly news programs to screen to audiences across Russia. Among these editors were four towering figures of Soviet filmmaking and montage: Lev Kuleshov, Esther Shub, Sergei Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov. Critic Yuri Tsivian writes: “Lev Kuleshov was among the first professional filmmakers engaged in the re-editing of pre-revolutionary films and it was on the basis of his experience as a re-editor that the famous 'Kuleshov experiment’s were devised.” Vertov is described as “the key figure in the early development of Soviet newsreel…” These re-editors were charged with transforming Western films for Soviet audiences both to reflect Marxist ideals and to confirm Soviet suspicions about western capitalism. Many western films were radically altered through sophisticated editing techniques, transformations in intertitles and complete excising of certain characters. Among the various changes re-editors were charged with making:

happy endings would be removed as suggesting that one can be happy under capitalism…"American endings" were generally believed to be forced upon artists by the capitalist film industry'… '[f]at and virtuous people were turned into villains as a general rule…. characters'nationality would be changed…

These daily transformations developed in editors, not only a sophisticated ability to analyze the political meanings of films but also mastery in the area of montage. It was during one such re-edit of Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse that Eisenstein first learned montage under another towering figure of Soviet film editing, Esther Shub. Soviet Filmmaker Sergei Yutkevitch recalls, “Eisenstein appointed himself [Shub’s] voluntary assistant in order to be able to study the construction of Fritz Lang’s montage.” It is here that we may see the birth of a generation of filmmakers rigorously educated in montage and concerned with the critical dialectics of their films. In these state sponsored editing activities the appropriation of film objects appears, purely as an accidental circumstance of the many cut-out shards of films saved by editors. These shards would come to be used in newsreel films or “compilation documentaries” as well as the experimental works circulating between editors and shown at private screenings for laughs.

In addition to these re-edited feature films was what has been variously called the “non-played film,” newsreel film, compilation documentary or the “real film.” In 1905 the Soviet Duma had begun financially supporting regional newsreels under the guidance of the official photographer of the Duma, Alexander Drankov. Once these newsreels were created, Marxist filmmakers, headed by Esther Shub began making passionate calls for a “non-played cinema” to facilitate an analysis and historiography of life under Tsarist rule before the revolution. The exemplary film of this genre is Shub’s The Fall of the Romanov Dynasty (1927). After seeing Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin Shub would “seek in newsreel material another film way to show the revolutionary past” by appropriating footage taken by Tsar Nicholas II’s court cameraman. The film, according to Shub was an enormous success with “queues…in all the big cinemas in Moscow.” It was the emergence of films like these that caused Vertov to suggest variously that “the history of Soviet cinema starts with experiments in newsreel film” and support these experimentations as a powerful alternative to film as entertainment when he wrote:

On the moviehouse habitué, the ordinary fiction film acts like a cigar or cigarette on a smoker. Intoxicated by the cine-nicotine, the spectator sucks from the screen the substance which soothes his nerves. A cine-object made with the materials of newsreel largely sobers him up, and gives him the impression of a disagreeable-tasting antidote to the poison.

The diametrical separation between films critically assembled from newsreels and the formalist “played film” frequently appears in the writings of Soviet editors. We may see in Shub’s project the use of film as documentary evidence to intervene and détourn the intentions of the film creator. When Nicholas II’s court cameraman innocently filmed images of dancing aristocrats, it was not for the purposes of contrasting these activities with the toil of ditch diggers that Shub edits into her film. It is Shub’s intervention which radicalizes film fragments that are themselves either apolitical or even counter revolutionary.

Another significant moment in Soviet filmmaking and its relationship to contemporary found footage is observable in a film script by Lilya Brik. Critic Yuri Tsivian notes:

[another] project comes from the pen of Lilya Brik (active in LEF through her connection with Osip Brik and Vladimir Mayakovsky) occasionally involved in script writing, acting and directing. Her first film script (as well as her first film part earlier), The Glass Eye, was a film about filming; her second script is lost, but Lilya Brik remembers it in her memoirs: 'Soon after [having finished The Glass Eye] I wrote a screenplay with a parodie title Love and Duty. The entire story of the film would go into the first reel. The other [four] reels would acquire a completely new meaning as a result of re-editing alone: ... - nothing to do with the original plot. Re-editing alone, not a single shot would be added!'.The style of the proposed film would change from one reel to another: sensational drama (boevik) - a film for teen-aged audiences soviet re-editing - American comedy. In the epilogue, tin cans with film would be shown rolling back to the film factory to be washed off - 'the suicide of film'."

Doesn't this script seem reminiscent of the constant reworking of films by re-cutters and mashers?

Friday, April 25, 2008

Total Recut Contest

The following is a release from the holy grail of remix sites:

TotalRecut.com is hosting a Video Remix Challenge over the next two months and we want you to create a short video using the theme: 'What is Remix Culture?' You can you use any footage you can find, including Public Domain and Creative Commons work, but the finished video cannot be longer than 3 minutes or shorter than 30 seconds long. The prizes include a Laptop computer loaded with video editing and conversion software, a digital camcorder, a digital media player, as well as Special Edition Total Recut T-Shirts, Books, DVDs and CDs. We have an amazing lineup of judges for the contest including Lawrence Lessig, Henry Jenkins, Kembrew McLeod, Pat Aufderheide, JD Lasica and Mark Hosler. You can find out more information at: http://www.totalrecut.com/contest1.php. Entries will be accepted from the 1st of May until the 2nd June 2008 when public voting will begin. The best 10 videos at the end of the 2 week voting period will be put forward into the final, where they will be voted on by the judging panel. The winners will be announced around the 1st of July. So get busy making those videos!

Here's a link to the YouTube promotional video for the contest: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tdgDTS3diGk

Thanks again for your support and participation in this and I look forward to hearing from you soon.

Thursday, March 13, 2008

Recycled Cinema for Cultural Borrowings Conference

Chevy Tahoe Commercial 2

10 Things I Hate About Commandments

Kodak Commercial

In the case of extra-time:

Shining:

Communist Manifestoon