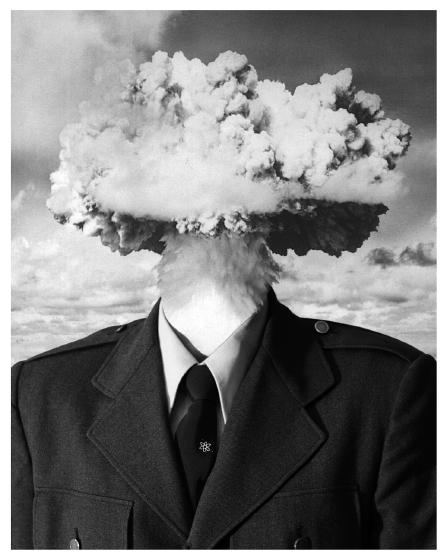

(Michael Snow's "Powers of Two" 2003)

(Michael Snow's "Powers of Two" 2003)Last night Jessica and I went to OCAD (Ontario College of Art and Design) to see Bruce Elder in conversation with Michael Snow. Snow, who was a contemporary of some of the most important avant-garde filmmakers, was known to me only through his film Wavelength and a few paintings I’d seen.

(Above Left: "Two Sides to Every Story", 1974 ; Below "In Medias Res" 1998)

The unifying principal I discerned from Snows paintings, photographs and installations was a sense of images and media as being sculptural. I was reminded of cinema studies critic Murray Smith, who writes in his essay “Modernism and the Avant-Gardes” that “Modernism represents the phase in the history of art when it reflects upon its materials and undergoes a kind of purification.” Snow may construct images, but the materials these images are placed over tends to take precedence over the images themselves. In the director of OCAD’s introduction to Snow and Elder, an old and prescient Snow quote is uttered (which I am forced to paraphrase because I was without pen and paper): “I have no interest in expressing myself. No interest at all. I am only interested in ways of seeing.” While I find Snow’s interest in form as well as content very much in line with one of my personal favorite literary movements, Modernism, his general apathy towards content seems to hint at a different aesthetic philosophy, which I will try to describe.

When Snow talks about film, he may be speaking literally, about film as the strip of frames with sprockets which when projected at 24 frames per second will appear to move because of the persistence of vision. When he talks about photographs he may be talking about 2 dimensionality, perspective, transparency and light. In other words, he is focused on the medium of the materials which disseminate images, rather than the images themselves. He refers to these thin slices of paper or long and narrow streams of emulsion as sculptural. He is very much the artistic embodiment of McLuhan’s adage that “the medium is the message.” Like the Modernists before him, Michael Snow reflects that phase in the history of film, when the film-maker reflects upon their materials.

After a long and exhaustive survey of Snow’s work, which while completely engaging was also about the length most attendees expected the entire talk to be (around an hour) Snow went on to show two films. The first, Shtoorrty (what happens when you combine “short” and “story”) manipulates time by superimposing two sections of a scene from an Iranian soap opera. The scene, is described here:

Fade in on a door. A doorbell rings. A beautiful young Woman answers the door. A young handsome Artist with a wrapped painting under his shoulder enters and hugs the beautiful Woman. She asks him to unwrap the painting, which he does. She admires the painting and asks the artist to show her Husband in the next room. They walk into the next room. The Husband, burly, ugly and foppish in an expensive suit admires the painting and asks the artist to hang it in the living room. Then the Husband says to the Artist, “Let’s drink to the painting, but not to you.” The Artist enquires why. The Husband states that he is aware his wife is having an affair with the Artist. The Artist makes a rude comment, which elicits the Husband too throw his wine in his face. The Artist takes the painting off the wall, and breaks it on the Husband’s head. The Artist heads for the door and the Woman says “goodbye.”

Beyond the fact that this scene may portray some subtle wish fulfillment on the part of Snow (the rich patron is scorned by his wife for the beautiful artist) its content is of little importance. Snow manipulates the film by superimposing the beginning of the scene over the middle, so that the scene is perpetual; it might be thought of as the cinematic counterpart to the row-row-row your boat chorus, which overlaps with the middle of the song. The mystery of the scene has been revealed upon first viewing, and the performances and cinematography require no more investigation by the audience. Instead, the audience becomes concerned with overlapping and placement of bodies. The double exposure represents two distinct moments in time meeting and breaking from each other. The result is a constructive effort to complicate a very simple narrative moment into an aesthetically complicated experiment with time. It is also notable for its use of found footage.

(Above: A still from Living Room, 2001. )

The next film, called Living Room comes from Snow’s *Corpus Callosum series. Though it feels at times like an expose of all the possible editing techniques and manipulations possible in video in the 1980s, though it was made in 2001. A lengthy conversation about the film is available here (http://www.horschamp.qc.ca/new_offscreen/snow_interview.html). Because of the relatively dated analog nature of the film, and its use of digital techniques I have seen performed expertly, I wasn’t terribly impressed.

The subsequent conversation with Bruce Elder shed some light on Living Room which I hadn’t considered. The conversation, which occurred somewhere around the 2 hour mark of the lecture represented that awkward moment when critic and artist converse. Snow’s discourse is terse and to the point, while Elder, a very articulate and brilliant scholar, tends to mine certain ideas and place them in a larger historical and philosophical context. Jessica felt like Elder may have been using the conversation to sententiously impress his own thoughts upon the audience. After one of Elder’s long insights into Living Room, a slightly befuddled Snow said “I just make em.” I was amused by the fact that few artists today would share Snow’s attitude. Most artists today are as engaged in criticism as their critics. They tend to be as well versed in art history and theory as those who deconstruct their work. Snow seems to be one of the last from the era of artists whose work comes from a more intuitive place. While Snow is in part a conceptual artist, (in that he is focused on the process of his art) his work can be understood outside of a conceptual framework. I had been lost in Elder’s effulgent descriptions of Snow’s work, when I remembered that mysterious element which attracted me to Snow in the first place. He just makes em’.

[1] Structural Film: “The structural film insists on its shape, and what content it has is minimal and subsidiary to the outline. Four characteristics of the structural film are its fixed camera position (fixed frame from the viewer’s perspective), the flicker effect, loop printing, and rephotography off the screen.” (P. 348 “Visionary Film" 3rd Ed., P. Adams Sitney, Oxofrd University Press, New York: 2002.)