Mashups, Re-cuts, and Machinema: The New Found Footage Filmmakers of the Internet

Once the exclusive province of the avant-garde and a few rogue outsiders, found footage filmmaking became a popular and widely emulated technique on internet media forums like YouTube in the last two years. Found footage filmmaking is the practice of appropriating or literally scavenging for footage and compiling multiple source materials together in a montage to construct a new film. Based on a hybrid of culture jamming[i] and detournement[ii], the technique as an art form came to fruition under the pioneering auspices of artists Joseph Cornell[iii] and Bruce Conner[iv]. This once obscure technique has found its way into the homes of millions of computer users in the form of online viral videos. While similar in technique, the found footage films of the internet have many marked stylistic differences with the found footage films from the avant-garde.

While the new found footage filmmakers of the internet have begun to develop superlative work, with their own sub-genres and technical innovations, impending legal battles have threatened to eliminate the distribution of these films. Unlike the found footage filmmakers of the past who found source materials in abandoned archives, thrift stores or literally thrown away in trash cans, the found footage filmmaker on YouTube tends to prefer well known, visible, and highly copyright protected images of mainstream Hollywood, TV shows, and video game screen captures. These tendencies emerge most likely from more than just the artistic fashions of the post-modern age. They are a direct response to the age of reproducibility we are currently living in. Digital media has made copying and manipulating media fast, cheap and easy to use. Abandoning the traditional tools of found footage filmmakers[v], the new cinematic appropriators have instead vied for the digital file and the Digital Video Disc (DVD). But while the ability to find source material has become easier, the law regarding its use has never been more steadfast.

In fact, the most notable distinction between the found footage filmmakers of the avant-garde and those of the Internet can be related to the choice of source material. While cinema appropriators of the past had little to fear in the way of copyright infringement suits from unmarketable, un-saleable films whose authors were often dead or unknown, the class of 2005 has graduated with the dubious honor of pillaging the most recognized media available. However the recognition of an established, popular piece of source material is intrinsic to the artistic, social and satirical value of new found footage films.

Another notable distinction between the found footage filmmakers of today and yesterday is parody. While found footage has a long history of parody, it has never existed so exclusively in this realm until now. The paradox of the new found footage style is that it must violate copyright in order to be an effective parody. Linda Hutcheon writes in her book, “A Theory of Parody”:

In order for parody to be recognized and interpreted, there must be certain codes shared between encoder and decoder. The most basic of these is that of parody itself, for, if the receiver does not recognize that the text is a parody, he or she will neutralize both its pragmatic ethos and its doubled structure[vi].

Parody requires the recognition of a reference—and because we live in an age where media is overwhelmingly controlled by private entities, it follows that most media that is part of the public consciousness is protected by a copyright. Within this paradox is contained the fuel for both sides of the legal battle over contemporary found footage filmmaking.

Most early found footage films are derived from what is commonly referred to as “ephemeral[vii]” media or footage. Due to the fact that the source material of early found footage films is usually unknown, the critical focus is on constructive properties. New found filmmakers transform well known source material, and so, the artfulness of the transformative process becomes the critical point of focus. In other words, the critical inquest becomes, “In what ways has the filmmaker played with music, scenes, and dialogue to present a well known film work, in a new way?” Unlike the antecedents of found footage, new filmmakers abandoned a conceptual framework and focused in on presenting reinterpretations of famous storylines, incorporating the most recognizable elements from several films, or, alienating the viewer from familiar films by altering genre or tone. In many ways, the “artiness” of found footage filmmaking has been abandoned in its co-optation of popular culture. To understand the social value of the new found footage filmmakers, I have elaborated on the categories, styles and contributions of various found footage films made for distribution on YouTube and other online video forums.

The most highly visible and imitated found footage techniques on YouTube today are mashups, re-cuts and machinema. Mashups combine multiple films to produce a cohesive work, often in the form of a film trailer. Re-Cuts usually take a single film or trope and alter it in several ways. One popular form of re-cut is re-genre, in which the tone, plot and genre of a film is altered by manipulating title cards, music cues, and selectively using scenes which when presented out of context serve the purpose of the appropriator. Machinema, a very recent development in found footage filmmaking utilizes screen captures from video games, which are later dubbed to produce a film.

Mashups

The term mashup, coined in Jamaica to describe destroying something was first widely used when referring to music. Employed most often in hip-hop, mashups described the combinations of a cappella tracks over new beats done by club DJs and on the radio. In the late 80s, John Oswald took this practice to another level when he released his album “Plunderphonics” (another early term for mashup) which utilized multiple pieces of source material put together in sophisticated patterns and combinations. The term has only been used to describe films in the last decade. Early forms of film mashups appeared in compilation films, though distinctions between the two have been made and will be elaborated upon later.

One of the most well known and controversial music mashups occurred in 2004, when Grammy winning hip-hop and alternative rock producer Danger Mouse did a mashup of The Beatles “The White Album” with rapper Jay-Z’s “The Black Album” called “The Gray Album.” This unification of highly disparate source material based entirely on a linguistic association has also entered the consciousness of found footage on the internet in the form of word associated mashups, which I will discuss later. The practice of the mashup has a long relatively uncharted history extending back to literature, and classical music. James Joyce’s epic tome “Ulysses” qualifies as a mashup because it places the themes and characters from “The Odyssey” into Dublin in 1904, introducing numerous other literary styles (women’s romantic literature, boys magazine writing, erotic sadomasochistic novels) into one narrative. Many famous pieces of classical music are the result of European folk songs expanded and altered to reveal complexities and variations. The Dadaists also performed literary mashup by utilizing aleatoric writing practices in which pieces of literature were randomly cut and pasted onto one page.

Behind the technical aspects of mashups, the practice of subverting a work of art by implying a new, often opposite or contrary meaning was a technique developed by the Situationist International called detournement. The practice of detournement has provided a wealth of creative works challenging the very source material employed in the work through manipulation. Most of the found footage films on YouTube display some level of detournement in their execution. While the spirit behind these works is more often playful than overtly political, they ultimately undermine and satirize the source material in a meaningful way. Many find it hard to seriously regard some of the seemingly sophomoric and juvenile works found on internet video forums, but as the technique has only been recently discovered, the most sophisticated applications in this arena have yet to be seen. One truly legitimate issue raised by all of these films is the apparent opposition to the clichés of modern cinema. In this way, YouTube mashups, re-genre and machinema strongly resemble the practice of “culture jamming” in their process undermining commercial cinema.

Mashup films can be broken down into several predominant styles and tropes. Most of the mashups found on the internet fall into one category and more or less obey the unwritten rules of that class of film. These categories, as I see them are: word associated mashups, which like Danger Mouse’s “Grey Album” unite two disparate source materials by a pun or joke found in the name; transgressive mashups, which transgress the sexual norms put forth in a film, often subverting hetero-normative portrayals; and overdubbing mashups, which use the images from a film and replaces the soundtrack with new dialogue or dialogue from another work, which undermines the original narrative.

Mashups based on word associations speak more than just for the wit of the appropriator. In principal, these mashups, when executed well, express some of the central creative tenets of modern found footage filmmaking: 1) Narrative film consistently follows the same filmic grammar and rarely diverts from it, making it easy to unify disparate films because of their similarities; and 2) the formulas inherent in narrative film are so well known by audiences that a few stylistic cues (which have been imitated to the point of cliché) can easily alert an audience to the nature of what they are watching. Using these two principals, mashups are highly successful at parodying more than just the films they chose to amalgamate, but also at critiquing and revealing the tools of narrative filmmaking.

Some exceptional word associated mashups include “Must Love Jaws” a combination of the romantic comedy “Must Love Dogs” and “Jaws” in which music cues and humorous scenes turn visual source material from “Jaws” into a story about a man who falls in love with a shark. Other superlative works include “8 ½ mile” in which Fellini’s 8 ½ is blended with the trailer for the Curtis Hanson, Eminem vehicle “8 Mile” and one of the greatest YouTube mashups I’ve seen, “10 Things I Hate About Commandments” in which Charlton Heston and Yul Brynner’s roles in “The Ten Commandments” are reduced to a petty High School tiff.

Ostensibly a kind of re-genre, transgressive mashups are crude, juvenile, sometimes vicious, and often droll subversions of the hetero-normative sexuality of films. The rise of YouTube fortunately coincided with the release of American culture-shocker “Brokeback Mountain.” The cause of intense derision, and equally impassioned pleas for tolerance months before the films actual release, the now canonical trailer for the film was, even for the open minded American film-goer, a bit shocking. Never before had two leading men played homosexuals on film demanding empathy rather than ridicule. The trailer was so solemn, so serious about the subject matter that it of course, demanded to be parodied.

Armed with the Gustavo Santaolalla score and the template for the Brokeback trailer hundreds of YouTube users constructed mash-ups of popular films with gay themes. Among the most notable is “Top Gun: Brokeback Squadron,” which puts together the most homoerotic scenes from Top Gun. Playing on Top Gun’s homoerotic subtext between Tom Cruise and Val Kilmer, (whose very casting was based on a picture by photographer Bruce Weber, famous for his homoerotic ad-campaigns for Calvin Klein and Abercrombie and Fitch) the film uses the “Brokeback Mountain” trailer template to tell a new imagining of “Top Gun” as a film about two Naval pilots who fall in love, but must keep their homosexuality a secret from their commanders and girlfriends. Other superlative work includes “Brokeback to the Future,” “Brokeback Mission” (Apollo 13) and “Brokeback Weapon.

Overdubbing, a tradition harkening back to Woody Allen’s “What’s Up Tiger Lilly?” and the Situationist International film “Can Dialectics Break Bricks?” has one of the longest histories of incorporating detournement into cinema. Overdubs have been employed most often using television to provide source material, frequently for political purposes to undermine an agenda or ideology. As of late, overdub has been rare—though the ease of employing the technique has kept it in practice.

Re-Genre and Re-Cut

Re-Genre films on YouTube often delve deep into iconic genre films and find the possibility of a new reading of the work. Re-genre places a traditional genre film into a new genus by manipulating music and selecting pertinent scenes to present a re-imagined trailer of a film. These transformative works play with the formulas and shibboleths found in Hollywood genres by showing the ease in which they can be manipulated to fit into new paradigms. Inventive re-genre films can pinpoint the subtle tricks employed in film trailers to inform an audience, often sub-consciously of exactly what kind of film they are watching the preview for. When done well, re-genre films completely invert the tone of a film.

The most widely seen re-genre film on YouTube manipulates the Stanley Kubrick adaptation of the Stephen King novel “The Shining” into a light hearted family film called “Shining.” The romantic comedy re-imagining of the film, constructed by Robert Ryang, a professional editor, depicts Jack Torrance (originally a character driven insane by cabin fever in a remote hotel) as an author struggling with writer’s block who meets a fatherless young boy named Danny (his son in the original film) and his mother (his wife in the original). Accompanied by Peter Gabriel’s sentimental rock song “Solsbury Hill” the trailer uses a voice over to transform the horror film into another genre—the family oriented romantic comedy. Utilizing dialogue from other films with Jack Nicholson, the flawlessly incorporated trailer could easily convince a naïve viewer of its authenticity. To the viewer in the know, it reveals the techniques of film trailers and genre. Machinema

Machinema (a portmanteau of machine and cinema) utilizes the images generated by video games to produce visuals for a film. The narrative of a machinema film is composed through overdubbing and selective editing. Instead of using the expensive computer generated images designed for big budget Hollywood films, the machinema filmmaker appropriates a pre-created 3-D computer generated environment and plays the game according to how the film will look. As is to be expected, some games can be controlled better than others. The video game “Sim Life 2” allows people to create their own films using avatars which move in a designed space. One of the most viewed films on YouTube, (3,111,692 views) “Male Restroom Etiquette” utilizes this Sim Life feature to describe the nuances of appropriate behavior in male restrooms. Utilizing computer generated avatars as actors, the film, designed as an instructional video, allowed someone to create a well developed, intelligent, humorous and wholly original film right at their computer.

Conclusion

Found footage emerged as an art form because of its powerful critical properties. It flourished because of the cheapness of the materials necessary to create found footage films. It has reappeared as an art form because of the powerful distribution platform of the Internet, and Internet video forums like YouTube. While the use of actual film footage to create a film required purchasing film stock, a flat-bed, splicing materials, and sound editing equipment, the new found footage films require nothing more than internet access. All the material and programs required to create a found footage films today can be downloaded over the Internet, creating an unprecedented ability for filmmakers to write, direct, produce and distribute their films. These new technologies have facilitated resurgence in a technique once only used by marginalized artists and filmmakers. As the tools to create these films become more accessible, the powerful properties inherent in found footage filmmaking will allow for a multitude of people without resources to make films.

[i] Culture Jamming: “I first came across the term in a 1991 New York Times article by cultural critic Mark Dery. It was coined by the San Francisco audio collage band Negativeland on their 1994 release entitled Jamcon ’84, as a tribute to jam radio “jammers” who clog the airwaves with scatological Mickey Mouse impersonations and other pop culture “noise.” Early culture jammers put graffiti on walls, liberated billboards, operated pirate radio stations, rearranged products on supermarket shelves, hacked their way into corporate and government computers and pulled off daring media pranks, hoaxes and provocations.” (P. 217, “Culture Jam: How To Reverse America’s Suicidal Consumer Binge—And Why We Must” by Kalle Lasn, Quill Publishing, New York, 2000.

[ii] Detournement is described as when “an artist reuses elements of well-known media to create a new work with a different message, often one opposed to the original. The term "detournement", borrowed from the French, originated with the Situationist International; a similar term more familiar to English speakers would be "turnabout", although this term is not used in academia and the arts world.” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Detournement)

[iii] Joseph Cornell: American artist and filmmaker. “Cornell’s first collage film, Rose Hobart, was made in the late 1930s…It represents the intersection of his involvement with collage and his love of the cinema; for Cornell had been for many years a collector of films and motion-picture stills. Rose Hobart is a re-editing of Columbia’s jungle drama, East of Borneo starring Rose Hobart. It is a breathtaking example of the potential for surrealistic imagery within a conventional Hollywood film once it is liberated from its narrative causality.” (P. 330, “Visionary Film” by P. Adam Sitney, 3rd edition, Oxford University Press, New York, 2002.

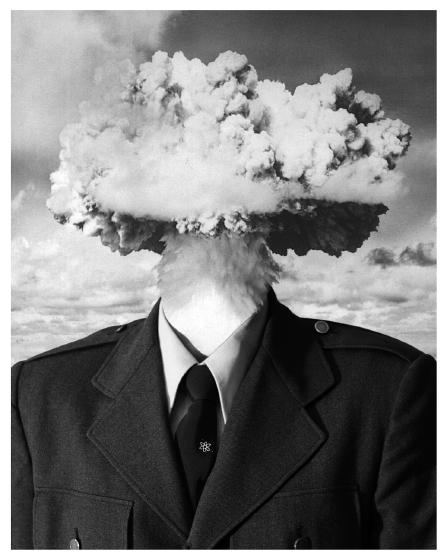

[iv] Bruce Conner: American artist and filmmaker. “Investing disparate shots with a kind of pseudo-continuity is one way of transforming found footage, as Bruce Conner demonstrates in a well known sequence of A Movie (1958): a submarine captain seems to see a scantily dressed woman through his periscope and responds by firing a torpedo which produces a nuclear explosion followed by huge waves ridden by surfboard riders.” (P. “Recycled Images: The Art and Politics of Found Footage Films” by William C. Wees, Anthology Film Archives, New York 1993.

[v] Traditional tools of found footage filmmakers would include film stock, a flatbed, splicing equipment, and sound equipment.

[vi] P. 27 “A Theory of Parody” Linda Hutcheon, Methuen, New York: 1985

[vii] “Critic Rick Prelinger uses the term ephemeral to describe films that are produced for a specific, short term purpose, then are normally discarded.” (p. 25, “Cut: Film As Found Object In Contemporary Video”, Lawrence Lessig and Rob Yeo, Milwaukee Art Museum, Distributed Art Publishers, New York: 2006.

1 comment:

Hello Eli,

I'm writing a paper at the moment about remix culture and how it has changed the concept of found footage. I was wondering if you have published this article somewhere, or if you have a newer version (from the Cultural Borrowings presentation for instance).

Since it says 'work in progress' at the top, I was thinking that you might have a newer version.

Thanks in advance!

Lotte Belice

Post a Comment